When it comes to traveling the Midwest, a visit to the South Dakota stone monuments of Mount Rushmore and Crazy Horse, is a must, along with a trip to Custer State Park and the Badlands. Unfortunately, Alan and I have yet to see them. What a shame!

hen our South Dakota road trip finally appears on the to do list, we’ll use the information that guest contributor, Vickie Lillo, shares in this article. We’ll arrive, not only knowing what to do, but with a deeper understanding of the historical significance of these National Park Service sites.

A small carving of Tennessee marble sits on a pedestal in the Crazy Horse Memorial Welcome Center. The carving portrays a warrior, Chief Crazy Horse, staring out across the sacred Pahá Sápa (Black Hills) of South Dakota.

Crazy Horse’s face is forged by dynamite blasting and skilled chiseling from the pink-tinted, fine-grained Harney granite of what was originally-named Thunderhead Mountain. It represents the collaboration between Chief Henry Standing Bear and Polish sculptor Korczak Ziolkowski. A project that would require the rest of their lives.

With the passing of Ziolkowski in 1982 (at the age of 74) and his wife Ruth, the 1st CEO of the non-profit Crazy Horse Memorial Foundation, several of their ten children carry on their father’s legacy. Along with the next generation of grandchildren, they continue to work in the museums and to replicate the image of Chief Crazy Horse, the epitome of the Sioux Nation.

After his capture, a white-man trader taunted Crazy Horse before his 1877 death with “where are your lands now?”

The warrior had answered mournfully, yet with defiance, “My lands are where my dead lie buried.”

Who better to represent Amerindians than Crazy Horse, the revered tactician who had led his Lakota brothers to victory at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876? The warrior is famous for his fighting prowess at Custer’s Last Stand, which Native Americans tout as a great win over a larger enemy.

Table of Contents

The invitation from Chief Standing Bear

Chief Henry Standing Bear (1874 to 1953)..a Brule Lakota from the Sioux Reservation…was a visionary. Or perhaps just the ultimate pragmatist.

Early on, he realized that he must learn non-Native ways, and develop cross-societal relationships, to best help his people. Warfare was NOT the route to preserving their rich culture…education and advocacy were.

He had even gone so far as to approach Gutzon Borglum, the Mt. Rushmore artist, to champion for the addition of a Native American representative to his Shrine of Democracy. The Chief would go to his grave before giving up on his hope for a memorial to his people in the Black Hills.

Eventually, Standing Bear became aware of Korczak Ziolkowski, a self-taught, master sculptor of Polish descent. The artisan’s marble rendition of Paderewski: Study of an Immortal, won first prize at the 1939 World’s Fair.

Standing Bear extended invited Ziolkowski to South Dakota to obtain his expertise in turning what used to be the peak at Thunderhead into a ‘hillside portrait’ of Crazy Horse, his maternal cousin.

“My fellow chiefs and I would like the white man to know the red man has great heroes, also,” he wrote in his petitioning letter.

After much deliberation, Ziolkowski accepted the Lakota’s offer to memorialize the accomplished Indian chieftain as a symbol of the spirit of all indigenous peoples..

“A little Polish boy from Boston? What an honor.”

Boomer Travel Tip

Looking for a place to stay? Check out the closest hotels to the Crazy Horse Memorial.

Envisioning the dream at Crazy Horse Memorial

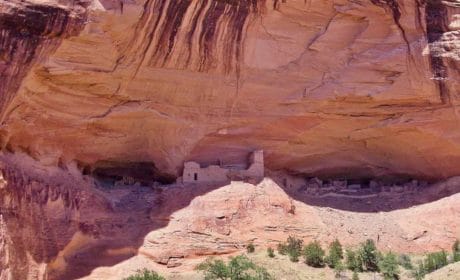

The initial blast occurred on June 3, 1948, whereby ten tons of rock were removed under the watchful eye of five survivors of the Little Bighorn conflict. Upon acceptance of Chief Standing Bear’s commission, Ziolkowski had arrived to the Black Hills…a land that appeared dark from a distance due to a profusion of evergreen trees, thus the name. He also arrived to no electricity or roads.

Living out of a tent in virtual wilderness for seven months, Ziolkowski constructed a home and passageways to access the cliff. With a mere $174 in the bank, he strove to immortalize the legend of Crazy Horse and uphold the mission of the future Memorial Foundation “to protect and preserve the culture, tradition, and living heritage of the North American Indians”.

With the help of Ruth Ross, a volunteer who became his wife, Ziolkowski set about fulfilling that dream. In the process, the two raised ten children in their small cabin home.

He liked to joke, “Every man has his mountain, I’m carving mine.”

A man of high principles and moral fiber, Ziolkowski never took a nickel’s worth of salary, working entirely free of charge. He financed the project solely through admission fees and donations.

With a degree of chagrin in 1949, he began charging a small entrance fee of 50¢ a person to defray the building expenses.

Ultimately, Ziolkowski built and operated both a dairy farm and lumber mill at the Crazy Horse worksite to support the project. No federal or state funds were ever accepted.

In fact, on two separate occasions, Ziolkowski turned down grants of $10 million from the government, afraid they wouldn’t complete the task in the manner he had promised.

“By carving Crazy Horse, if I can give back to the Indian some of his pride and create a means to keep alive his culture and heritage, my life will have been worthwhile.”

The storyteller of stone monuments

Thus, Ziolkowski became a “storyteller in stone. May his remains be left unknown.” So reads the epitaph on his tomb door, at the base of the landmark, with both the letters cut from steel plate and the words of the inscription manufactured by his own hand.

Initially, he chopped out 741 steps to the top of the Crazy Horse commemorative. For seven years, he lugged all his equipment up them every day…often climbing several times in a morning, as he’d have to descend to restart Buda, the old and decrepit air compressor at the bottom that powered his drill.

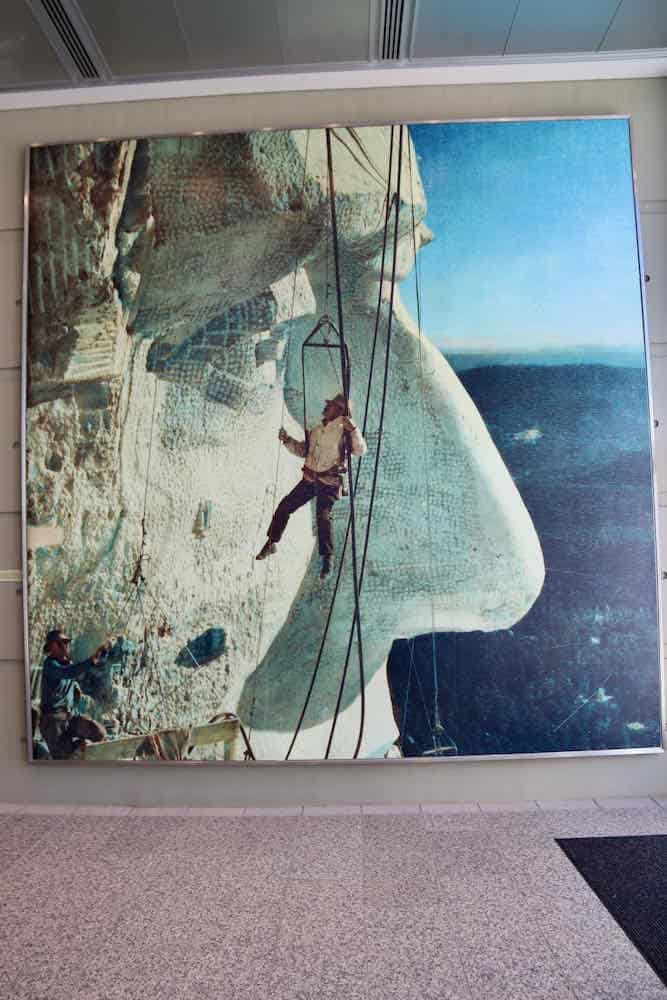

To make his vision more visible, Ziolkowski outlined the sculpture on the mount, using 164 gallons of white paint. While his wife Ruth, with Crazy Horse Mountain’s measurements and binocs in hand, directed him by radio from the Visitor Center, he illustrated the sketch, nearly a mile away, secured from a rope dangling over the side.

Visiting Crazy Horse Memorial

My husband Gustavo and I use our binoculars to study the carvers working on the world’s largest mountain sculpture in progress today located in Crazy Horse, South Dakota. The workers are nearly ¾ mile from the Welcome Center’s parking lot. Toiling year-round, the crew works with chisels; labor-intensive drilling, feathering and wedging to remove rock; and tedious wire-saw cuts.

This phase: finishing Crazy Horse’s left appendage—the arm, hand and the extended index finger, which will rest on the horse’s mane. When completed, the task that began in 1948 to create the 563-ft. high, 641-ft. long tribute will dwarf Mt. Rushmore. All four presidents, in fact, will actually fit inside the Indian chief’s 87.5-ft.-tall head.

What to see at Crazy Horse Monument: The Welcome Center, three museums, and infinite artifacts

The 40,000-sq.ft. Welcome Center/museum complex (official website), run by staff members and Ziolkowski offspring, contains hundreds of artifacts. Most belonged to the Oglala Lakota Sioux Tribe, from the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in the southern part of Badlands National Park.

Artwork depicting eagles and the bison herds, of Native Americans riding horses like their ancestors, grace the walls. Paintings on animal-hide, embellished with rabbit fur, wood and colorful pigments, hang alongside buffalo heads, illustrations, and ceremonial dress memorabilia.

Old-timey images, photographed by David Humphreys Miller (who lived amongst the Amerindians of the Dakotas and their neighboring states), queue in rows in a gallery dedicated to Custer’s Survivors from the skirmish known to the Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass.

Mementos, large and small, line the glass shelves: knife sheaths, pipes, tomahawks, and tambourines; horseshoes and arrowhead remnants from the battlefield itself at Little Big Horn; buckskin bandolier bags (the original cross-body satchel), hats, moccasins, and decorated baby buntings.

Even dolls. Specifically, Katsina (or Kachina) dolls from the Hopi tribe, created for ceremonial purposes and given to the children.

“Every doll would have a spirit,” explains Donna Zopp, Visitor Center staff member.

Typically fashioned from cottonwood root, these effigies were used to instruct young girls and new brides about the katsinam – the immortal, kindhearted spirit beings who brought rain.

Black-white-and-red bird masks decorate a wooden display case. A roped-off equine mannequin cloaked in intricately-beaded horse regalia, stitched by Douglas Fast Horse, stands proudly next to an exhibit of pottery. A birch-bark canoe, sealed with pine pitch and treated with bear grease to hold out water, dominates at least 1/3 of the gallery.

Both The Indian Museum of North America and the Native American Educational and Cultural Center, here on-site, act as a storehouse for Amerindian arts and crafts, and relics.

After strolling the multiple museums and the aisles of the gift shop, Gustavo and I return to the Welcome Center. We stare at the monolith from the enormous Wall of Windows, where my in-laws (who made the trip to South Dakota with us) are still admiring the attraction, before heading to the Outdoor Viewing Veranda for a slightly different angle.

Boomer Travel Tip

Start planning your next national park trip with our National Park Travel Planner!

Watching Lakota Cultural Presentations

Once outside, we find a vacant seat for the upcoming cultural presentation (offered daily from May through September). A girl-duo performs a fancy shawl dance, while a young Lakota man entertains with feather dance.

The performances are followed by amazing Hoop dances, intermingled and braided together to represent different animal interpretations. A series of movements and rhythms utilize hoops to tell a personal story. Obviously, every dance is distinctly unique in nature.

Starr Chief Eagle informs us that butterflies and eagles will inspire her performance. Using the spirit name that embodies her personality, Brave Star Woman, given to her by the elders.

She identifies as Rosebud, Lakota, and Sioux. This means she’s from the Rosebud Reservation; her language is the dialect Lakota; and she belongs to the Sioux Nation.

“We are a living, breathing culture.” Times may change, she notes, “But we will adapt and go on.”

As she prepares her 20 hoops, Starr Chief Eagle addresses her clothing. “This is my regalia…it is NOT a costume. It’s part of our identity, it’s who we are.”

Pointing to beadwork on her regalia, she adds, “We have access to new materials now. Many of these beads were traded for.”

An even older tradition than beadwork was quillwork, an ancient skill plied by Native American artisans. It was used primarily by the Plains Indian tribes who adorned their war shirts, dresses, and buffalo robes with dyed porcupine quills.

Starr informs the audience, “Sometimes it takes months…or years… to make a person’s regalia.”

Carrying on traditions

Brave Star Woman continues to explain the ways of the Amerindians.

“We greet any one we meet with the same respect as a grandparent or a family member.”

So, traditionally, there are no orphans, because everyone garners the same respect as a member of one’s family. ensuring “There would always be someone to take over.”

Strains of music waft out from behind the curtain.

“We don’t want to be disrespectful to the earth, plants, or animals,”

She begins to enumerate the conventional, indigenous philosophies of hunting…of tracking and killing the prairie’s bison.

“First, we take only what we need. Second, we use everything.”

Nothing is wasted. Tendons and sinews are used to make rope and bowstrings. The bladder will make water containers. Hooves and bones becmoe honing tools and weapons. Even their manure is useful burned as fuel for cooking and heating.

“And third, we thank the buffalo, afterwards.” For sacrificing its life so that its human counterparts might live.

Chief Eagle begins picking up the brightly-hued hoops with her feet, maneuvering them up her body and over her head. She intertwines them…lacing the hoops together…then plucking them apart.

From backstage, wails and chanting emanate, along with the thrumming of drums. A band from Canada, ‘Northern Creed,’ accompanies her dancing with original song, many of the lyrics sung in the local language.

As the culture show concludes, I look back across the great expanse, towards the Amerindian etched in the granite. I can still see signs of that white paint, though faded, that Ziolkowski splattered against the side of the rock to physically sketch-out the symbol of his inventive genius.

And I’m confident that Crazy Horse will one day be brought to life on old Thunderhead Mountain, as a majestic hero galloping his thundering steed into battle. Just as Chief Henry Standing Bear and Ziolkowski imagined. Sadly, not in my lifetime, though.

Boomer Travel Tip

Looking for a national parks books reading list? Here are our recommendations for 52 of the Best National Parks Books.

Mount Rushmore Memorial: testament to democracy

Just up the road from the Crazy Horse Memorial, but still within the Black Hills, sits another stupendous mountain carving – the shrine at Mt. Rushmore. A quartet of 60-ft. Presidential faces…George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and Theodore Roosevelt…stand as stone memorials to democracy.

With noses rendered 20-ft. long, eyes 11-ft. wide, and mouths, another 18-ft. in width, the individual sculptures signify, respectively, the struggle for independence and birth of the United States.They also represent territorial expansion; permanent union of the States and equality for all citizens; ending with world affairs, plus the rights of the common man.

Hewn from the same Harney Peak granite as Crazy Horse, the stone is full of crystalline veins called pegmatite that are susceptible to cracking. President Jefferson’s likeness was originally designed to sit on Washington’s other side. As it turned out, the boulders were weakened by these unevenly-cooled, transparent seams, and his face had to be blasted from the strata and relocated.

Gutzon Borglum, sculptor extraordinaire and ever the perfectionist, experimented with observation. This required long periods of time, to visualize the effects of light and shadow on the façade of Mount Rushmore.

This resulted, in due course, in the turning of the head of Washington about 20° further to the south than initially intended. The change permits the sun to fall on the North side of the Founding Father’s countenance as late as 1:00 p.m.

An idea in stone emerges

In 1923, South Dakota state historian, Doane Robinson, suggested the notion of a cliffside carving to bring tourists to the Black Hills, since the terrain here is not particularly conducive to farming. Agriculture, at this time, was the main economy of most of the rest of South Dakota.

His idea of sculpting the Needles (several natural granite pillars just north of current-day Custer State Park) into real-life, historical protagonists of the West (like Sioux chief Red Cloud, who signed the Ft. Laramie treaty) was met with complete skepticism and criticism. Except by Gutzon Borglum, who was then working on another picture in stone…the likeness of Confederate General Robert E. Lee on Stone Mountain in Georgia.

Borglum conceptualized Robinson’s dream, transforming the potential tourist attraction into a memorial to the ideals of democracy.

Believe it or not, the original estimate to complete the project was five years and $500,000. Instead, the monument took 14 years to complete, right up to the onset of WWII, at a cost of $1 million.

Unfortunately Borglum died before seeing the finished project and what has become a national treasure that draws millions of vacationers to the Black Hills every year.

Boomer Travel Tip

Plan your trip: the 10 closest hotels to Mount Rushmore.

The Sculptor and his muses

The Mt. Rushmore Preservation Fund, established to safeguard America’s monument to the ideals of democracy and freedom, still accepts donations. I personally love their slogan plastered on the wall inside the museum: “If they were dictators, they wouldn’t ask for your support. They’d demand it.”

After all, maintaining the Presidential physical attributes…from skull to chin…. is a constant concern. Minor surface blemishes insist on immediate attention. Whereas, in the past, linseed oil and a mixture of granite dust and white lead were used to repair the crevices, today’s restoration crew applies caulk with silicone sealant.

The repairs are not just to protect the portraits in stone from the elements. They also uphold Gutzon Borglum’s dream that the four granite figures he chiseled on the mountain…his muses, if you will…remain “until the wind and rain alone shall wash them away.”

Born in Idaho, in 1867, to Mormon Danish immigrants, Borglum was raised at the end of the 19th century in America’s wild-and-woolly Western frontier. In an epoch replete with overwhelming national confidence and illusions of territorial expansion, Borglum often jumped on that bandwagon, expressing those characteristics in his work.

An outspoken activist, he immersed himself in politics, domestic and international. Borglum began the designing of Mt. Rushmore National Memorial in 1925, at the ripe age of 58.

“A monument’s dimensions should be determined by the importance to civilization of the events commemorated.”

Sculpting Mount Rushmore into a work of art

The personification of art and engineering, Mt. Rushmore was created, using newfangled methods…dynamite and pneumatic hammers…alongside the typical drills and chisels for demolition. Every single inch of those iconic faces was blasted out of the mountain with sticks of explosive nitroglycerin.

Besides the sculptor, the ‘pointer’ was the most important person of the troupe. His job was to tell the workers exactly where to dynamite, cut, hammer, etc.

These skilled laborers teetered over the side of the cliff with their jackhammers, suspended by swing seats and harnesses. They timed their explosions to occur just before lunch break and again at 4:00 p.m., the official end of the day.

Overall, to complete the tribute, it required nearly 400 workers…about 30-40 people hired each summer…mostly plucked from the ranks of the unemployed. The carvers clocked in every morning at 7:30 a.m., only after the arduous 700-stair climb to the top, earning an hourly pay ranging from 35¢ to $1.50.

“More and more we sensed that we were creating a truly great thing,” explained Otto ‘Red’ Anderson, driller and assistant-carver.

“And after a while all of us old hands became truly dedicated… and determined to stick to it.”

Altogether, they detonated around 450,000 tons of rock from Mt. Rushmore, which still lays crumbled at its base. Finishing touches were performed by hand, to ensure that the surfaces would be smooth as concrete. Called ‘bumping’, this evening-out of the granite was the final phase.

Borglum also appointed Professor Walter Long as the Refiner of Expression, to perfect the Presidential facial features and adjust the lighting and shadows just so, in order to make them recognizable.

Unveiling of the Faces, One by One

“People like dedications,” announced Gutzon Borglum, as they prepared to unveil the first of the finished faces, “And if you don’t get people out here, nobody is going to know what you got.”

Indeed, Washington’s head…commanding a view to the east, to capture the dawn’s first light…was undraped the 4th of July, 1930, a fitting tribute on Independence Day to venerate the Chief Executive’s devotion to personal and civic freedoms.

For Jefferson’s dedication, August 30, 1936, incumbent President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared, “I had seen the photographs and the drawings of this great work, and yet, until about ten minutes ago, I had no conception of its magnitude, its permanent beauty and its importance.”

He concluded that “this can be a monument and an inspiration for the continuance of the democratic republican form of government, not only in our own beloved country, but, we hope, throughout the world.”

On the 150th anniversary of the adoption of the U.S. Constitution, September 17, 1937, Lincoln’s head was unveiled.

The final unmasking of Theodore Roosevelt occurred on July 12, 1939, having secured a niche in the Mt. Rushmore pièce-de-resistance partly for his role as a consummate conservationist. During his two terms in office, Teddy set aside approximately 230 million acres as wildlife refuges and national forests.

And unbeknownst to most, the possibility for a fifth luminary on the mountain, that of a woman…suffragist and activist, Susan B. Anthony…was submitted as a bill to Congress in 1936. Unfortunately, the House Appropriations Committee required that funding would only go towards sculptures already in progress. So the application was quickly nixed.

Death of the Sculptor

In 1941, Gutzon Borglum died, having worked on the Rushmore project for 17 years. His son Lincoln officially finished it, though the end-result never completely encompassed his father’s vision.

In the beginning, sculptor Borglum’s 1935 conception called for a large inscription (the Entablature) of significant dates in America’s history, plus a grand public stairway leading from the valley at the foot of the mountain to a large repository (the Hall of Records) behind the presidential heads.This chamber of information would tell the story of Mt. Rushmore and the United States.

The sculpture itself was already considered “a work of art for the ages,” with its 60-ft faces. But when the undertaking ran out of both good-quality Harney granite and money, these additional plans for inscriptions and a repository were scrapped.

The impending American involvement in WWII, along with that lack of funding and unsuitable rock, caused the drilling on the stone to stop. On October 31, 1941, the memorial was declared 100% finished.

The controversy, however, will never be finished. Still today, many Native Americans denounce this blight upon their hallowed land.

Some even protest against the Crazy Horse Memorial, dedicated to promoting the true Indian spirit, and their wisdom. In the eyes of these antagonists, NOTHING…nor anyone’s likeness…should deface the sanctity of their hills.

Visiting Mount Rushmore

Gustavo and I, plus my inlaws, get our first glimpse of the presidential figures as we round the last bend at the overlook off Hwy 244 out of Keystone, South Dakota.

Once parked, we start our journey at the Avenue of Flags, an expansive sidewalk flanked by 56 flags. They represent all 50 states, 1 district, 3 U.S. territories and 2 commonwealths, with plaques commemorating the year each was admitted to the Union. This nice touch was added in 1976 as part of America’s bicentennial.

From the amphitheater viewing deck, we get our first close-up of George, Tom, Teddy, and Abe. The day’s natural light is beginning to dim, ever so slowly, splaying a color wash…really only a shadow…across the eyes and forehead of the 1st President of the United States, George Washington.

In a few more hours, after dusk, the entire engraving will be illuminated, a nightly occurrence during the summer.

I’ve heard the ice cream on the premises is a don’t-miss attraction. It’s President Jefferson’s private recipe.

Explore the Lincoln Borglum Visitor Center

To start our tour, the best place is the Lincoln Borglum Visitor Center (official website). The four of us take in the 14-minute documentary film, Mt Rushmore: The Shrine, which highlights the carving of the monument and the realization of Gutzon’s dream.

Photographic displays, tool exhibits and some of the original large equipment fill the museum. At the Sculptor’s Studio, we are able to view the initial 1/12th-scale model of the actual busts, down to their waistcoats, as he had first illustrated them.

Walk the Presidential Trail

We follow the Presidential Trail, a ½-mile loop that affords an up-close view of the sculpture, for most of the distance, bypassing some of the 422 stairs.The vista from the Borglum View Terrace is lovely, but not great for pictures staring into the late afternoon sun.

Repetitious flickers of shimmering light peek through the Ponderosa pines that dominate this craggy landscape of the Black Hills. A profusion of spruce trees dapples the talus slope…the mound of slag at the base, cast-off from the years of blasting.

Spring wildflowers…golden pea, wild blue flax, bergamot and prairie cone flower…are already on the wane. We did see a white-tail browsing on a sapling on our way to Rushmore, but no elk or mule deer.

A charming, striped chipmunk, scampering willy-nilly at the amphitheater, amused us when we first arrived. We hoped to stay for the evening illumination ceremony, held about 9:30 nightly during the summer months, but I began to feel the effects of substituting only soda and snacks for lunch.

I’d like to take this opportunity to warn visitors: in case anyone gets a ‘wild hair’ during the visit and plans on climbing the memorial…think again.This has been officially prohibited, in other words, it’s illegal, since work ended there in 1941.

In fact, even Hitchcock had to shoot his famous chase scene in the 1959 thriller North by Northwest on a replica built in a Hollywood studio.

It’s easy to see why Borglum chose Mt. Rushmore as the backdrop for his masterpiece. Mother Nature, for eons, had already laid her glorious hand upon the topography.

Native American tribes had each left their unique signature on the Black Hills.

Famous frontiersmen Wild Bill Hickock and Buffalo Bill Cody, along with Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid…outlaws equally-renowned in their infamy…had all stamped their imprints on this remarkable stretch of South Dakota wilderness.

Gutzon’s four muses, on the Shrine of Democracy, will remain for all time…or until they disintegrate into dust…as a grand statement about the endurance of our nation and the legendary status of the American West.